Site 13. The Great Escape

Flight Lieutenant Alastair Donald Mackintosh “Sandy” Gunn was born in Auchterarder on the 27th September 1919. With the clouds of war looming, Sandy signed up with the RAF Volunteer Reserve in 1939, and was called up to serve his country in June 1940. By July 1941 Sandy was operational and flying missions protecting the incoming convoys of food and supplies from the USA. August saw a move to Stornoway where Sandy proved himself an excellent navigator over large expanses of water, so much so that he came to the attention of his commanding officers and was selected for a role in the Photo Reconnaissance Unit. Arriving at RAF Benson in September 1941 he learned to fly a Spitfire, and with just a handful of flights he was over targets in Germany and Denmark photographing the dockyards and ship movements of the German Kriegsmarine.

January 1942 saw six men tasked with finding the battleship Tirpitz, Sandy amongst them, and to do so they were seconded to RAF Wick. On the 23rd January Tirpitz was found in Trondheim Harbour and Enigma intelligence suggested that the ship was likely to move at any time and the Luftwaffe presence was building up to protect the battleship. Bomber Command would need to strike hard and fast to eliminate the threat, and having eyes on Tirpitz was essential whenever flights could be made. It was on this mission that Sandy was at the controls of Spitfire AA810 on the morning of Thursday the 5th March 1942.

AA810 was a Supermarine Spitfire PR.IV which was a photo reconnaissance version of the well-known icon of the Battle of Britain. This would only be its 16th mission since being delivered to the RAF on the 19th of October 1941. In place of its machine guns, AA810 was fitted with extra fuel tanks which allowed it to carry an extra 66 gallons per wing on top of the normal 85 gallons which was in the fuel tank fitted between the engine and the pilot. This increased fuel load meant that the Spitfire PR.IV had an impressive 2000 miles range, but the additional tanks and weight of this extra fuel required all the guns and armour-plating to be removed, leaving the Spitfire defenceless.

At 08:07, AA810 lifted off from Wick’s runway headed for Norway. After a brief stop at RAF Sumburgh on Shetland to top up his fuel tanks Sandy headed east across the North Sea. As Sandy approached Trondheim at 25,000 feet (7600m) his Spitfire’s Merlin engine started playing up. Arriving over Trondheim Sandy’s attention was fully immersed in what was happening in the cockpit as he tried to determine the cause of his engine problems.

Unbeknown to him, two Messerschmitt Bf109’s of Jagdgruppe Losigkeit had been scrambled from Lade Airfield in Trondheim and were waiting for him over the fjord. Leutnants Heinz Knocke and Dieter Gerhardt, flying as a pair, descended upon Sandy with Knocke reporting hits destroying the oil system of the Spitfire. Such was the nature of the one-sided battle that Heinz got close enough to have his windscreen obscured by oil from AA810 and therefore it was Dieter who closed in to make the kill as Sandy dived away to the southwest. Dieter’s rounds found their mark and soon Sandy’s aircraft was on fire.

Leaving it as long as possible, Sandy bailed out suffering burns to his hands and his face in the process. He descended by parachute landing on the hills above Surnadal not far from where his Spitfire had impacted the snow covered mountain. Assisted by locals, Sandy attempted to make good an escape on skis but, with his descent being witnessed by the German garrison and the distance and elements against him, his chances were very limited indeed. Sandy’s German captors treated him well, and the next day he was on a lorry to Trondheim before being flown to Germany via Oslo. Interrogated at Dulag Luft transit camp for almost a month, he was sent to the new prisoner of war camp of Stalag Luft III near Sagan, being the fifth prisoner to arrive.

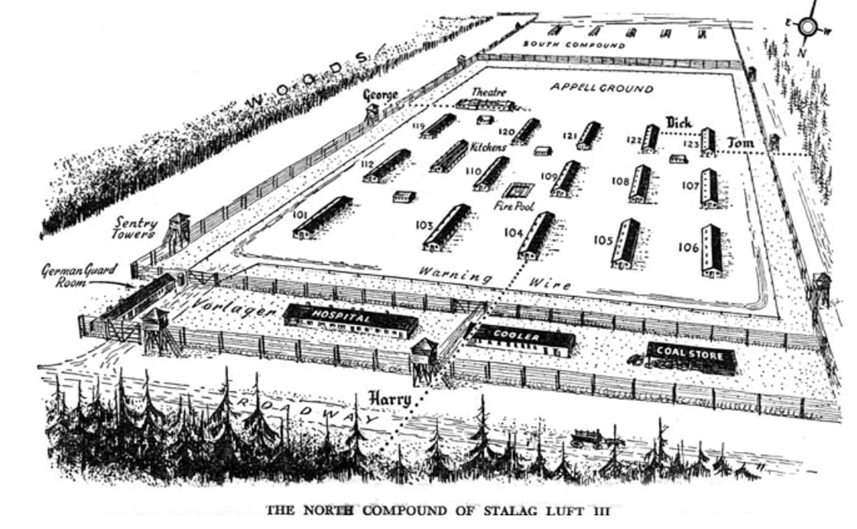

Sandy was not on his own for long, and soon found himself billeted with a number of men whose names were shortly to become very famous. Guy Griffiths, Arnošt (Wally) Valenta, John Boardman, Des Plunkett, Dudley Davis and Hubert Henderson all shared the hut with Sandy. Everybody had their own jobs in the camp and Sandy’s found a role as a Security Officer guarding the escape committee conferences from German sentries. Even more secretly Sandy was a tunneller. Although the first tunnel was discovered, he was soon put to work on a second longer tunnel, codenamed Harry, which was to become known the world over.

The Escape Leader, Roger Bushell, realised that he stood to get only 200 men from the camp in his escape attempt, even though nearly 600 had been involved with the whole escape planning. The first 100 men to escape would be those who had contributed the most to the project, whilst the second 100 would be decided by lottery from the remaining 500. The first 30 handpicked men were either fluent German speakers or were paired with those who were, and were considered the ones most likely to have a successful ‘home run’. Sandy was picked to be number 68 paired with Mike Casey.

So it was on the night of the 24th March 1944 that the men gathered in hut 104 and prepared to leave. Unfortunately the tunnel was too short causing delays and a backog in the escape. With the sheer number of men moving through the tunnel, it suffered several collapses, one of these occurring on Sandy who had to be pulled out. Soon however it was Sandy’s turn and together with Mike they disappeared into the night. Just seven men later the tunnel was discovered.

As soon as the tunnel was discovered, the Germans swung into action. Several roll calls were made and it was clear that 76 men had left the camp that night. Hubert Henderson had to double back in the tunnel and spent considerable time in solitary confinement as a result. Sandy and Mike however, were away and intent on making their way to the German port of Sassnitz to jump on a boat to neutral Sweden. Instead of riding in passenger trains, he and Mike decided to ride underneath the freight trains as they continued their journey away from the camp. Sadly about 25 miles from Stettin late on the 26th March they were both discovered and arrested.

Adolf Hitler was infuriated by the escape so all the recaptured prisoners were handed over to the Gestapo and transported to Görlitz for interrogation. Sandy and Mike were held with a number of other escapees from the camp, including Roger Bethell to whom Sandy recounted his escape story. The men were all called forward over the coming days, repeatedly questioned on their escape attempt or to give information about the processes within the camp, but all remained silent.

Hitler wanted all of the recaptured prisoners to be executed, but fearing reprisals against Luftwaffe prisoners in allied hands, Goering convinced Hitler to only have 50 of the recaptured prisoners executed. Slowly, as the number of men at Görlitz dwindled, Sandy’s name was called once more on the morning of the 6th April. Expecting to be put through further interrogation he was instead bundled into a Gestapo car and was seen being driven out of the prison. Unknown to his colleagues he was shot later that day. Sandy’s remains were cremated, and his ashes returned to Stalag Luft III.

Sandy now rests in peace alongside his fellow murdered prisoners in the Commonwealth War Grave Cemetery in Poznan, Poland.