Site 21. P for PIP

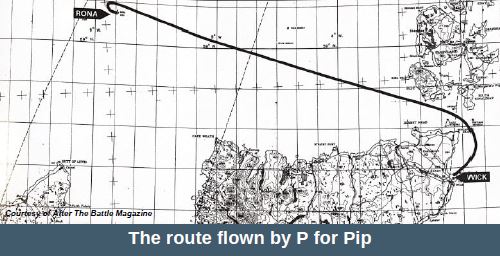

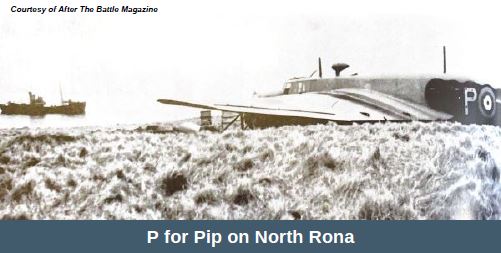

On the 23rd of April 1941, a very unusual event occurred involving Armstrong Whitworth Whitley, ‘P for Pip’, of No.612 Squadron, (WL-P, T4321). A test was being conducted of the newly installed and very secret ASV Radar (Air to Surface Vessel) to see if it could be used as a homing device with the Wick MF/DF Beacon (Medium Frequency Direction Finding). It was estimated that the system would work at some 60 to 80 miles distance, so it was decided that the aircraft should be flown as far as North Rona, a small island about 100 miles from Wick, then turn around and see at what distance the radar could pick up the beacon as the aircraft approached its home base.

Wing Commander Wallis was in the pilot’s seat. After taking off from Wick a strong easterly wind blowing down the Pentland Firth helped him make good time to North Rona, but as he approached the uninhabited island the co-pilot, Flying Officer Hatchwell, pointed excitedly to the underside of the port Merlin engine. Oil could be seen gushing out from a point forward of the propeller boss. From experience Wing Commander Wallis knew that the problem was a fractured oil feed pipe to the variable pitch propeller, and that he only had about 10 minutes before the engine would seize. So common was this problem on the Whitley that Wallis had experienced this very same problem just two months previously. However, on that occasion the engine had actually caught fire.

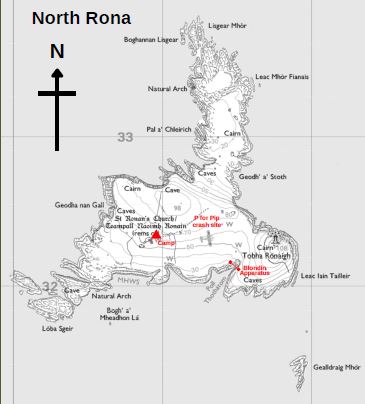

As the crew braced for the crash landing there was a moment of panic as a gust of wind raised the port wing, edging the aircraft towards the southern cliff face. However, the strong wind was their saving grace, and the ground speed of the Whitley was down to only 40 knots as they touched down, making a textbook wheels-up belly landing. The aircraft slid only a few yards before coming to a stop, the crew being extremely relieved to have survived. A quick check was carried out and it was discovered that not a single injury had been incurred by the crew. The ignition and fuel were shut off and the crew rapidly evacuated the aircraft in case there was a fire or explosion. However, the smooth landing had caused minimal damage to the aircraft and no such occurrence happened. After five minutes the crew returned to the aircraft and were delighted to find that the wireless transmitter had also survived and was still in working order.

A radio call was put out for help and a HSL (High Speed Launch) from Shapinsay was scrambled, but it would be at least 4 hours before it could reach North Rona. With a nice touch of wartime humour a message was relayed back to the crew informing them that the HSL had set sail, but what was humorous about the message was that it was addressed to the “A.O.C. North Rona” (Air Officer Commanding). At this time Wing Commander Wallis sported a very impressive handlebar moustache, and one of his NCO’s claimed he saw one of the many seals that call North Rona home, draw itself up out of the water, salute, and say “Good morning, sir!” The crew kept a watch for German U-boats in case one attempted to land on the island to investigate the strange-looking aircraft. If a U-boat had been sighted the crew would have destroyed the top secret ASV equipment immediately. Unfortunately, by the time the HSL reached North Rona the weather conditions had deteriorated considerably so the crew of ‘P for Pip’ had to spend the night on board the launch as it took shelter in a cove on the west side of the island. The following morning the weather conditions had eased which allowed the HSL to head for Scrabster where the crew were landed safely.

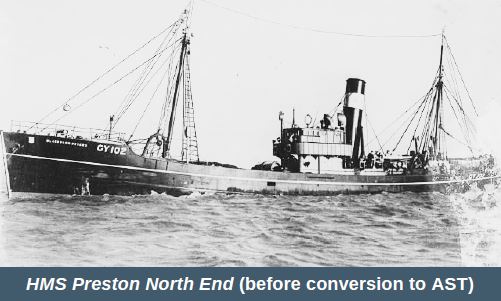

The crash landing carried out by Wing Commander Willis was so textbook that the aircraft was not a total write off. However, it was located on a remote uninhabited island with steep seacliffs and it was decided that the top secret radar equipment and valuable Merlin engines should, at the very least, be recovered. A recovery team, consisting of one officer, six NCO’s and twenty airmen, from 68 Maintenance Unit at RAF Carluke, near Glasgow, were despatched to Scrabster in the 1st week of May. The team, with all their recovery equipment and supplies, was collected by the Anti-Submarine Trawler HMS Preston North End. Once landed on North Rona the recovery party set up a camp and an inspection was made of the aircraft. It was reported back to RAF Carluke that “Whitley T4321 Cat B and engine may require more than a shock test. Air Screws badly damaged and major damage to the underside of the fuselage and to the flaps. Skin wrinkled badly adjacent to the centre section”.

A further message was then sent to Flying Officer Nisbet, Engineering Officer, 612 Squadron at RAF Wick, which read, “Your suspicions regarding the Air Screw pipelines confirmed by examination. The pipe RA1617 is located on the port side of the engine and you will note that when tightening the banjo union the tendency is to twist the pipe in towards the spinner. In my opinion this has occurred on this particular engine and the union clip has also fractured as a result of chaffing and the locking strip has released the pipe sufficiently to make contact with the spinner”. The recovery team spent all day on the 8th of May removing the ASV radar equipment and this, along with the damaged oil pipes from the engines and the pyrotechnics from the aircraft, were sent back to Wick on board the Preston North End.

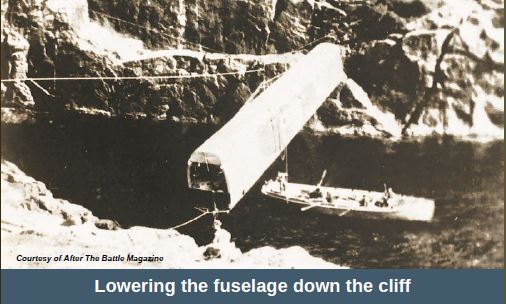

The initial plan had just been to remove the two Merlin engines. However, due to the considerably light damage to the airframe it was decided that the entire aircraft should be recovered. It took the recovery team just seven days to remove the two engines, remove both wings, and split the fuselage into 3 sections. The Preston North End , along with the small drifter HMS Mist , would make regular stops at the island with fresh supplies. However, bad weather often hampered all attempts to land on the Island and the recovery team would have to resort to frying seagull’s eggs when the fresh supplies ran low.

The dismantled aircraft sections were slid along baulks of wood dug into trenches until they reached Poll Thothatom Cove, some 1000 ft away from the crash site. Rigging and an aerial cableway were set up using Barrage Balloon steel wires fitted with Blondin Apparatus, and the sections of aircraft were lowered down the cliff face to a waiting boat below. The aircraft sections were then hoisted onto the deck of the Preston North End. By the 21st of May, the recovery operation was complete and the Preston North End set sail back to Wick Harbour where it was met by the Armstrong Whitworth representative based at RAF Wick who examined the sections of the dismantled aircraft. He was amazed at the remarkably good condition the aircraft parts were in, considering what they had been through, and congratulated the team on a job well done. He estimated that the salvaged parts had a value of some £12,000(£645,500 in 2024) and they had even managed to retrieve 500 gallons of valuable petrol from the stricken aircraft.

The aircraft sections were then transported the short distance to RAF Wick before being sent to ‘Air Work Services’ at RAF Gatwick where they were reassembled, repaired and returned to flying condition. By December 1941, T4321 was returned to the RAF and in 1942 was put into operation with 10 OTU (Operational Training Unit), based at RAF St Eval, where it was used to train Coastal Command crews. It was finally retired from service in July 1944. A Whitley had never been split in half in the field before, and for his efforts during this operation the recovery party’s commanding officer, Pilot Officer Davis, was awarded an M.B.E.

However, the story does not end there, the recovery team found a partially decomposed human skeleton in a naval uniform lying in the ruins of an old church on the island. A small cairn had been built by the sailor with a piece of cloth tied to it to try to attract attention. It was believed that the sailor had been there for at least 5 months. However, a search of the remains yielded no papers or dog tags for identification, so the recovery crew left it in place. They named him ‘George Rona’, but it is now believed that the body is that of Acting Sub-Lieutenant P. N. Hopper RNR, of HMS Intrepid, who had been washed overboard in a Force 8 gale. His body was never recovered, and to this day it still lies within the ruined church on North Rona. Sub-Lieutenant Hopper was only 20 years old and is commemorated on the Chatham Naval Memorial.